Living With The Penguins: Operation Deep Freeze And The Nivada Grenchen Antarctic

Nivada Grenchen is one of those “rebirthed watch brand” success stories. Today’s story, however, comes from the 1950s. First founded in 1926 in Granges, Switzerland, Nivada Grenchen went from strength to strength in the mid-20th century. Pioneering tough self-winding timepieces, Nivada Grenchen was one of the first companies to use the technology in 1930. Unfortunately, like so many other brands, the company went bust during the Quartz Crisis. Fast-forward to today, and it has been successfully revived.

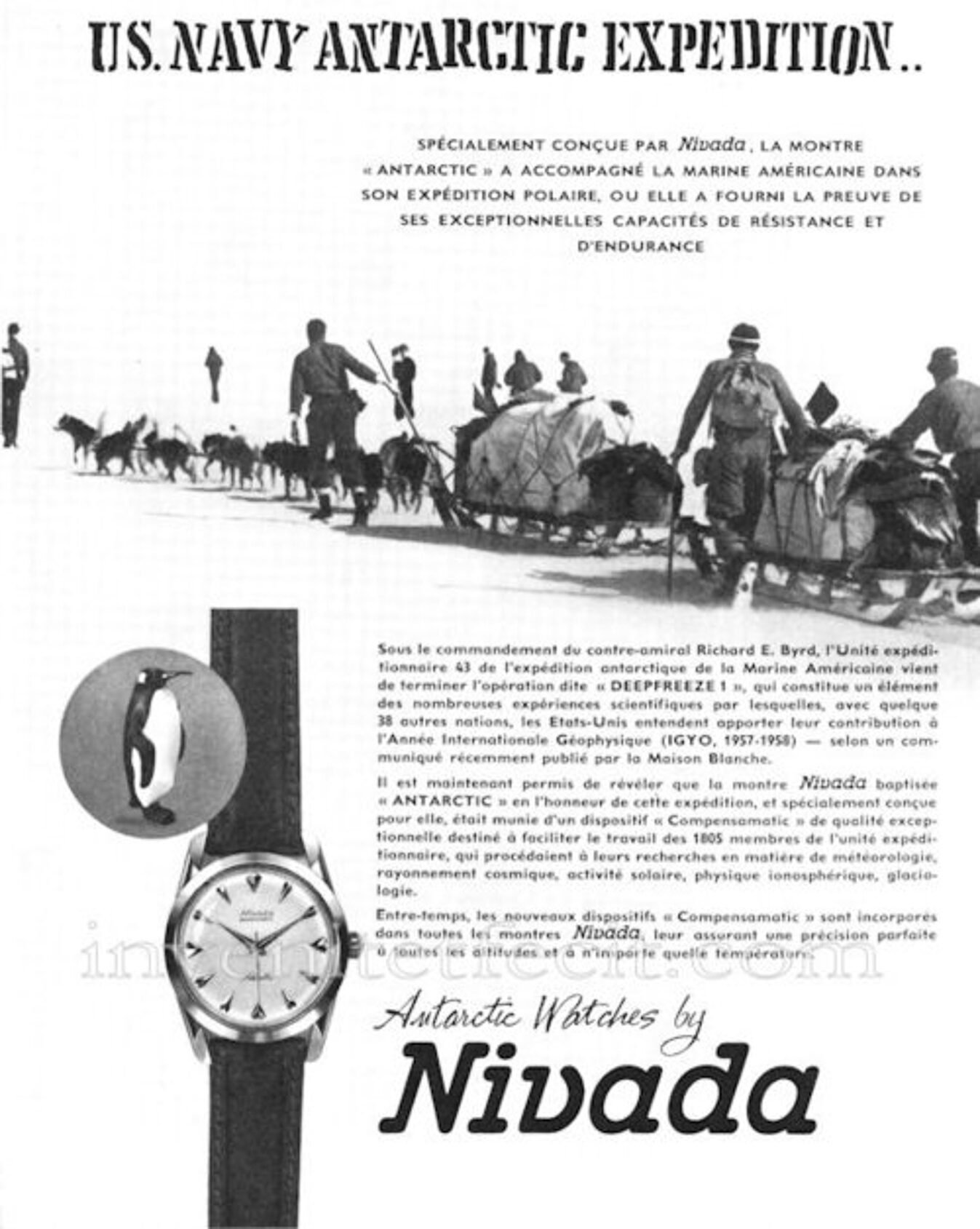

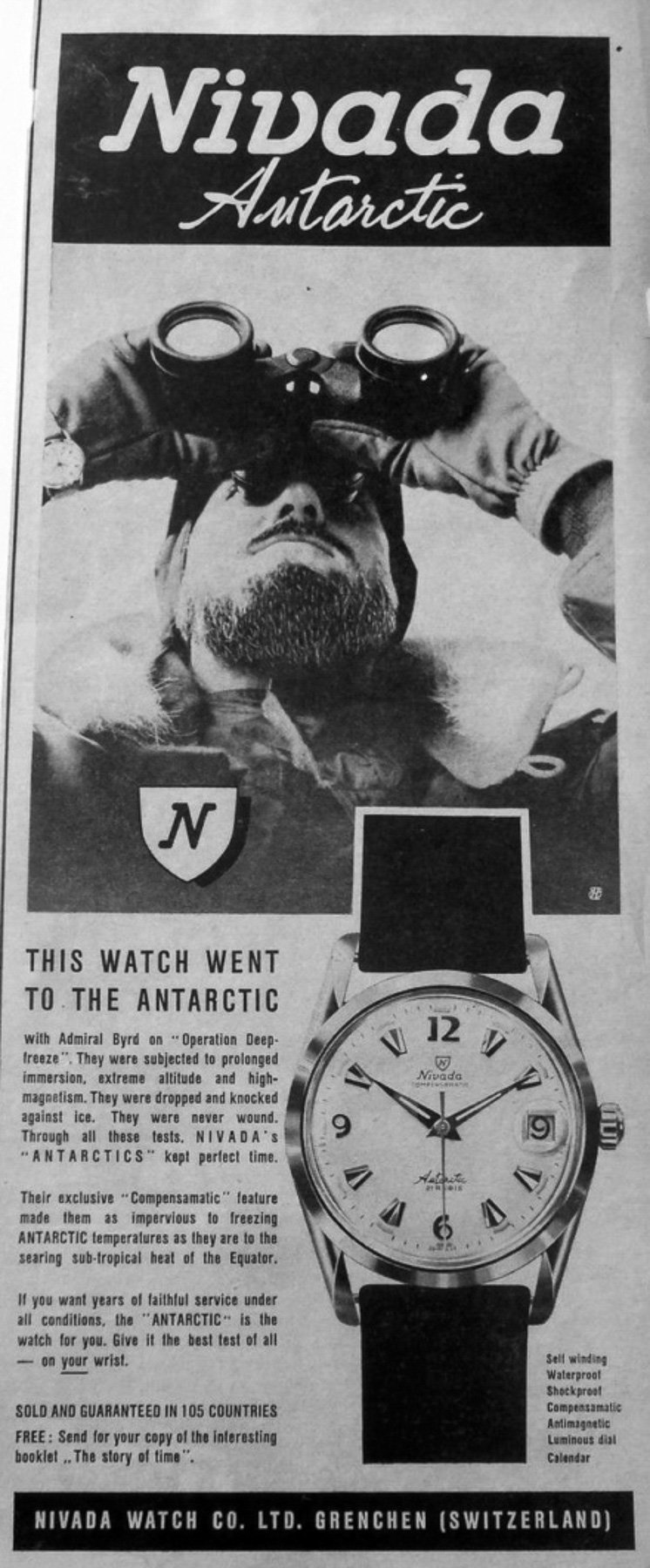

One of the leading timepieces that Nivada Grenchen produced was the Antarctic, which debuted in 1950. It is also one of the brand’s leading model lines today, with multiple iterations, including a hand-wound 35mm example. The original Antarctic was a mid-sized (for the time), durable, and “waterproof” daily watch. The company put its claims of durability to the test by providing the watch to the members of the American Navy’s Operation Deep Freeze I during their expedition to the South Pole.

Just by chance, I stumbled across a unique photo archive that shows the Nivada Grenchen in action amid the extreme conditions of the Antarctic. Our thanks to the holders of the Oliver L. Austin Photographic Collection, Florida State University, for putting this wonderful series of images on digital display for the education of all. These images were curated by Dr. Annika A. Culver and donated by Anthony “Tony” Austin.

A decade of scientific discovery

The period from the late 1940s right up to the start of the 1960s was one marked by enormous scientific advances. As the historian Tony Judt noted in his book Postwar, much of this period was marked by the competition between the Cold War powers (in particular, the United States and the Soviet Union). Amid this context, during the 1950s, these powers declared the International Geophysical Year (IGY). This would mark a collaborative scientific effort that would involve these nations sending teams to explore the Earth’s extreme environments, including the north and south poles.

Nivada Grenchen steps in

Watch companies were keen to match this scientific progress. Thanks to advancements in wristwatch technology, manufacturers could produce timepieces that were more resilient to the tough conditions that explorers faced. Nivada Grenchen was one of those watch companies that wanted to have its timepieces on the wrists of adventurers.

As part of this period of exploration, the US Navy began a series of expeditions to the Antarctic under the codename Operation Deep Freeze. Nivada thus decided to provide a “waterproof” and antimagnetic wristwatch to accompany the Navy’s scientists and researchers. The brand used this in all its advertising at the time and was quite successful. Nivada ran into trademark issues over its name, so you will find watches branded Nivada Grenchen, Croton Nivada Grenchen, and simply Nivada from this era. You may remember Balazs’s review of the 35mm Nivada Grenchen Antarctic reissue. Thankfully, there are also original photos from these expeditions, which give us a very real sense of what these watches would have endured.

Operation Deep Freeze

The first Operation Deep Freeze mission took place in 1955–56. Operation Deep Freeze II, Operation Deep Freeze III, and many others would follow until 1998. According to Wikipedia, “the impetus behind Operation Deep Freeze I was the International Geophysical Year 1957–58,” although the mission predated it. In any case, the US along with New Zealand, the United Kingdom, France, Japan, Norway, Chile, Argentina, and the USSR agreed to go to the South Pole, the least explored area on Earth. US government records state that their objective was to learn more about “Antarctic hydrography, weather systems, glacial movements, and marine and bird life.”

As part of Operation Deep Freeze, the US Navy was in charge of supporting the American scientists for their portion of the IGY studies. US Navy records note that Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd, who had been on four previous Antarctic expeditions, led the effort. Task Force 43 was created to provide logistical support. It included nine vessels, various freighters, tankers, and specialized icebreakers.

Extreme conditions

The American scientists had to brave extreme weather conditions during their stay. One of them was Dr. Oliver Austin, a renowned ornithologist and Curator of Ornithology at the Florida Museum of Natural History. According to his biography online, Dr. Austin got a PhD from Harvard University, and then, after serving in the US Navy in World War II, he went to Japan, where he worked in the Allied Military Government for Occupied Territories. For Operation Deep Freeze, Dr. Austin worked as a US Air Force scientific observer with the US Navy. He also researched Adelie penguins and other wildlife during his tour. In one image taken from his earlier time in Japan, we can see a highly intelligent face staring back at us.

Luckily for us, Dr. Austin was (seemingly) also a keen photographer. By chance, while researching a completely different story (coming soon to Fratello!), I stumbled across Dr. Austin’s photo archive of Operation Deep Freeze, which has been digitized thanks to Florida State University. In those photos, we can see the American scientific team grappling with boredom, playing what seems to be baseball on the ice — with a penguin watching on — as well as capturing and conducting scientific analysis on local birds and marine life.

A photo archive to remember

In the incredible color images, Penguins seem to be a predominant theme, with one even looking on rather nonchalantly at a baseball game. The photos also show the remains of the British Nimrod Expedition of 1907–1909, otherwise known as the British Antarctic Expedition, including long-surviving food rations. The wonderful photo archive provides a sense of what it must have felt like to be in that icy wilderness — very alone, very cold, but wondrously beautiful.

A sense of humor

In this environment, a sense of humor would have been key to keeping spirits high. One image shows a sign jokingly referring to the camp as “McMurdo Heights Summer Resort.” The resort advertises “Good people – low prices. Air[-]cooled rooms – Continental cuisine.” Forbiddingly, no baths or women are allowed. In another image, we see a sign pointing to the South Pole, reminding us that was never far away. A third image shows a sign that states: “There’s no place, any place like this place, anywhere near this place, so this must be the place.”

The scientists on Operation Deep Freeze truly were at the edge of the known world. Even with modern(-ish) helicopters and icebreakers, it could easily have been a life-threatening situation if something seriously went wrong.

Importantly for this story, in the image above, you can even see a Nivada Grenchen Antarctic on the wrist of one of the scientists as he measures a bird.

Art captures life

Some wonderful works of art also captured camp life thanks to the presence of two artists — Robert Charles Haun and Commander Standish Backus — aboard Task Force 43. According to the US Navy Naval History and Heritage Command museum, Haun focused many of his sketches on the work of the Mobile Construction Battalion. Before Operation Deep Freeze, he had painted murals for the Naval Air Station on Rhode Island. Haun also designed the emblem for Operation Deep Freeze I. You can see some of these sketches here and the full body of work here.

The Americans were eager to carry out their mission when they landed as part of Operation Deep Freeze. According to one account: “Men swarmed down the gangway as soon as it was lowered. Cargo crews hoisted all ‘topside’ cargo by boom to waiting crews on the bay ice. Among the first items to be landed were huge sleds to carry freight and huge tractors to pull the sleds. Thus[,] freight could be loaded direct[ly] from the ships’ holds onto waiting sleds and rushed to a temporary supply dump almost halfway between shipside and campsite. While this 24-hour-a-day cargo shuttle was running, crews bridged crevasses between the supply dump and the base sites. Surveyors worked to lay out a five-acre site that would spring up as Little America Five.”

Difficult, dangerous, and sometimes deadly work

Crevasses were a serious concern for the US personnel during Operation Deep Freeze. According to US Navy accounts, even today, crevasse-detection methods are laborious and dangerous, and this was even more the case with the equipment available in the 1950s.

According to historical records, “Richard T. Williams, CD3, USN, a heavy[-]equipment driver of MCB (Special)[,] was killed when his D8 Caterpillar crashed through a bridge that had been placed over a crack in the ice at McMurdo Sound. A few weeks later, tractor driver Max R. Kiel fell victim to a huge crevasse while also driving a D8 tractor. These were the only two fatalities during Operation Deep Freeze I. In memory of these men, the Air Operating Facility at McMurdo Sound was named Williams Air Operating Facility[,] and the airstrip at Little America V became Max Kiel Airfield.”

An advertising milestone for Nivada Grenchen

The Nivada Grenchen Antarctic survived the harsh conditions of the frozen South Pole. The company went on to heavily advertise the watch’s use during this mission in newspaper advertisements. One advertisement claimed: “They were subjected to prolonged immersion, extreme altitude and high-magnetism. They were dropped and knocked against ice. They were never wound. Through all these tests, Nivada’s ‘Antarctics’ kept perfect time.” And so they did!

Purely by chance, some of Dr. Austin’s photos show the Antarctic in action in these difficult conditions. Importantly, these pictures were not part of an advertisement. Rather, they were part of one man’s contribution to science, and what incredible memories they must have represented to him. Dr. Austin died in 1988.

Final thoughts

Thanks to the curious and brave souls who pushed the limits of endurance, we have wonderful images and artwork archives like those that covered Operation Deep Freeze I. Life in the Antarctic was about as close to living on the Moon as humans could get. This was dangerous and sometimes very lonely work, but these scientists and navy personnel pursued their mission with integrity and diligence.

But what do you think, Fratelli? Is there any particular adventure like this one that we should look into? Let us know in the comments.